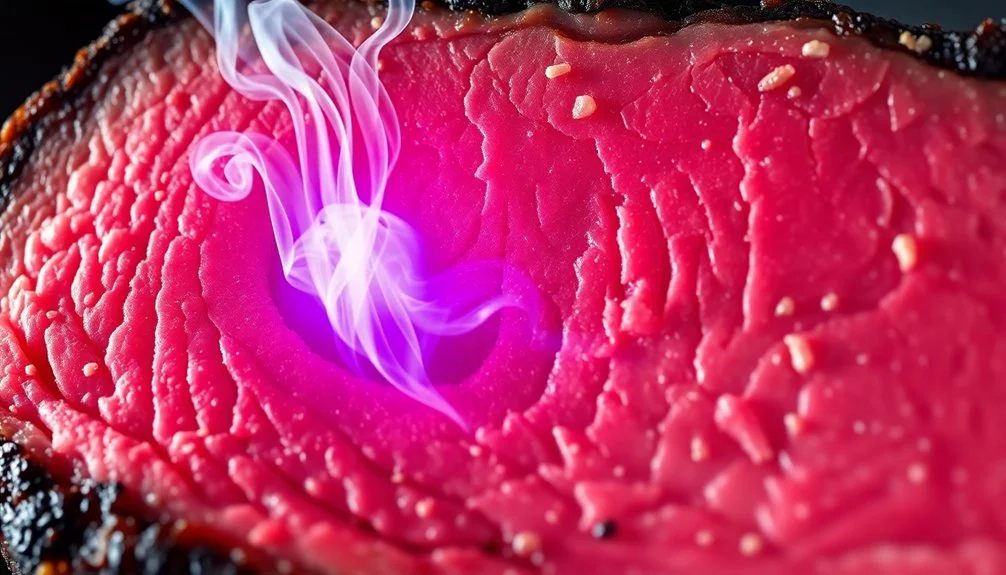

Smoke molecules bond with your meat's proteins through multiple chemical reactions during the smoking process. When smoke hits the meat's surface, both fat-soluble and water-soluble compounds begin to interact with proteins. Fat-soluble molecules penetrate deeper into the meat's structure, while water-soluble compounds attach to surface proteins. Heat causes proteins to denature and reshape, creating new binding sites for smoke compounds. The Maillard reaction then occurs as proteins break down into amino acids and bond with sugars, forming complex flavor compounds. These transformations permanently lock in smoky flavors and create that distinctive pink smoke ring you're looking for. The science behind this process reveals even more fascinating chemical interactions.

The Chemistry Behind Smoke Compounds

The complexity of smoke's chemical composition makes it a fascinating subject in food science. When you're smoking meat, you're actually working with hundreds of different chemicals, including carbon compounds, tar, oils, and various volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These components are produced through incomplete combustion, where there isn't enough oxygen to burn the fuel completely.

You'll find that smoke formation depends heavily on temperature, oxygen levels, and the type of fuel you're using. Whether you're burning wood, charcoal, or other materials, the pyrolysis process creates distinct chemical compounds that will affect your final product. The smoke's composition changes based on your environmental conditions, including ventilation and distance from the source. The transition to pure carbon charcoal results in significantly less smoke production during the cooking process.

During the smoking process, you're initiating multiple chemical reactions simultaneously. Free radicals participate in redox reactions, while the Maillard reaction occurs between amino acids and reducing sugars, creating new flavor compounds.

The process also involves caramelization of sugars in your seasoning rubs. Carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide from the smoke interact with the meat's myoglobin, creating that characteristic pink ring that's prized in smoked meats.

Protein Structure and Smoke Interaction

When you smoke meat, specific compounds in the smoke interact directly with myoglobin proteins, causing them to form new chemical bonds and change color.

You'll notice that smoking triggers protein denaturation, where the proteins' natural structures unfold and reshape as they're exposed to heat and smoke molecules.

These structural changes in meat proteins aren't just visual – they fundamentally alter the meat's texture and create new flavor compounds through chemical reactions with the smoke. These protein modifications are similar to those seen in studies showing slight structural changes in proteins associated with various diseases.

Myoglobin Binding With Smoke

Inside every piece of meat, myoglobin molecules play an essential role in smoke ring formation by binding with specific compounds from wood smoke. When you smoke meat, the combustion of wood or charcoal produces nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), which penetrate just below the meat's surface.

These gases interact with myoglobin's iron component, creating a distinctive pink color that won't fade during cooking. Understanding myoglobin is crucial since it accounts for 75% of meat weight in muscle tissue.

You'll notice that myoglobin's behavior changes based on its environment. In high oxygen, it's bright red; in zero oxygen, it's purple; and in low oxygen, it's brown. However, when NO and CO bond with myoglobin, they create a stable pink color that persists even as the rest of the meat turns gray from heat.

This reaction typically occurs within the first 30 minutes of smoking and stops when the meat reaches about 170°F.

The depth of your smoke ring depends on several factors. You'll get better results with meat that's high in myoglobin (like beef compared to chicken), fresh, and cold when you start smoking.

You should also trim excess fat since it can block NO and CO from reaching the underlying meat before oxidation occurs.

Protein Denaturation During Smoking

Smoking's intense heat triggers an essential process called protein denaturation that fundamentally changes your meat's structure. When temperatures reach 105°F to 125°F, the heat begins disrupting hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions within the proteins, causing them to unfold and lose their natural shape.

You'll notice significant changes in your meat's texture as smoking continues. During the process, proteins become less soluble and start clumping together, while water evaporates from the meat. If you smoke your meat for 90 minutes, you'll typically see the lowest protein content due to increased water loss and denaturation compared to shorter smoking times of 60 minutes.

As you smoke your meat, chemicals from the smoke interact with the proteins, forming new bonds and affecting their functional properties. These reactions, combined with changes in pH levels, influence how the proteins behave.

The longer you smoke your meat, the more extensive the denaturation becomes, potentially leading to tougher, drier meat. While smoking enhances flavor through the Maillard reaction, extended smoking times and high temperatures can damage proteins, reducing their nutritional value and affecting the meat's water-binding capacity.

Smoke Ring Formation Process

The chemical dance between smoke molecules and meat proteins creates the coveted smoke ring, a pink-colored band that forms just beneath the surface of smoked meats. When you burn wood or charcoal, it releases nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO), which are essential for this process.

These gases interact with myoglobin, a protein in the meat's muscle cells, to create carboxymyoglobin, giving the smoke ring its characteristic pinkish-red color.

You'll get the best smoke ring formation when you maintain proper moisture on the meat's surface, as this helps the gases penetrate more effectively. The process works best with meats that have high myoglobin content, like beef and pork, though excessive fat layers can block the gases from penetrating.

To maximize smoke ring development, you'll want to start with cooler meat and use the low-and-slow cooking method, giving the gases more time to interact with the myoglobin.

Keep your dry rub layer thin and consider using a water pan to maintain surface moisture. While you can enhance the ring using ground celery seed or curing agents, avoid acidic substances that might interfere with the process.

Temperature Effects On Protein Bonds

Heat's transformative power on meat proteins begins with a delicate cascade of molecular changes.

You'll see the first signs of protein denaturation at relatively low temperatures of 30-32°C, where myofibrillar proteins start to unfold. As temperatures climb to 36-40°C, these proteins begin associating with each other, leading to gelation when you reach 45-50°C.

When you're cooking meat, you'll notice significant changes in collagen structure between 53-63°C. At this point, collagen fibers contract and can potentially dissolve into gelatin if they're not stabilized.

You'll get better results with low-temperature, prolonged cooking, as it helps maintain collagen structure and moisture content.

The protein transformation doesn't stop there. As temperatures rise further, you'll see increased protein aggregation and cross-linking, which affects how easily your body can digest these proteins.

The myofibrillar proteins undergo a shift from α-helix to β-sheet structures, and you'll notice decreased moisture content from 72% to 65%.

These changes directly impact the meat's texture, tenderness, and nutritional value, so controlling your cooking temperature is essential for ideal results.

Volatile Compounds and Flavor Development

When you smoke meat, volatile compounds interact with proteins and fats through both physical absorption and chemical bonding, creating complex flavor profiles.

You'll find that fat-soluble smoke molecules penetrate deeper into the meat's structure, while water-soluble compounds bond with surface proteins to form new flavor compounds.

These interactions transform the protein structure through heat-induced changes, allowing aromatic compounds to become permanently bound to the meat's matrix, resulting in that characteristic smoky taste.

Smoke Absorption Through Fat

Through intricate chemical interactions, smoke molecules encounter considerable barriers when attempting to penetrate fat layers during the smoking process. You'll find that NO and CO, essential components for smoke ring formation, can't effectively pass through thick fat layers to reach the underlying meat. That's why you'll get better results by removing most of the fat cap before smoking.

While fat can't absorb smoke molecules efficiently, it does play a key role in flavor development. You'll notice that fat acts as a storage system for various compounds, including alkanes, alkenes, aldehydes, and aromatic hydrocarbons. These compounds contribute to your meat's overall flavor profile, even though they don't enhance the smoke ring formation.

When you're smoking meat, the type and thickness of fat greatly impact how smoke penetrates the meat. You'll achieve better smoke absorption with thinner fat layers, and you'll want to maintain a moist environment to enhance smoke adherence.

The marbling within muscle fibers will still contribute to tenderness and flavor, but excessive external fat will block those desirable smoke compounds from properly bonding with the meat proteins.

Chemical Bonds During Cooking

The complex formation of chemical bonds during meat smoking goes far beyond simple fat absorption. When you smoke meat, volatile compounds interact with proteins through Maillard reactions, creating a symphony of flavors through aldehydes, carbonyls, furans, and other aromatic compounds.

As your meat heats up, proteins denature into amino acids, which then bond with sugars in those essential Maillard reactions. You'll notice this process intensifies around 60°C/140°F when collagen begins transforming into gelatin.

The smoke particles follow air currents and deposit flavor molecules that chemically bond to the meat's surface, following first-order kinetics.

What you're tasting is actually a precise chemical dance – the breakdown of fats into sugars and fatty acids combines with denatured proteins to create new flavor compounds. The speed and temperature of cooking dramatically affect these reactions.

If you cook too hot or fast, you'll drive out water and fat before the collagen can properly convert to gelatin, leaving you with tough meat. The key is allowing enough time for these chemical bonds to form properly, ensuring both tenderness and ideal flavor development.

Aromatics Impact Protein Structure

Smoking meat releases a complex cascade of aromatic compounds that fundamentally alter protein structures at the molecular level. When these volatile compounds interact with meat proteins, they trigger changes in the proteins' secondary and tertiary structures, affecting both functionality and digestibility.

You'll find that these interactions aren't just surface-level changes – they're transforming the meat's molecular makeup through Maillard reactions and lipid oxidation.

As you smoke meat, the volatile compounds, including aldehydes, ketones, pyrazines, and thiophenes, bind directly to protein structures. These bonds affect how your meat retains and releases flavors. The proteins' ability to bind with specific aromatic compounds determines the intensity and character of the smoke flavor you'll taste.

You're actually witnessing a complex interplay where phospholipids and triacylglycerols break down, creating new flavor compounds that attach to the modified protein structures.

The temperature of your smoke and cooking duration greatly influence these protein-volatile interactions. When proteins denature during smoking, they expose hydrophobic sites and undergo aggregation, which directly impacts how the meat holds onto smoke molecules and ultimately affects both texture and flavor development.

Myoglobin's Role in Color Change

Understanding meat's color changes starts with myoglobin, a protein that acts like a molecular chameleon in response to oxygen levels.

You'll see myoglobin shift between three main states, each with its distinct color. When there's no oxygen present, you're looking at deoxymyoglobin's purple-red hue, typical in vacuum-sealed packages. Expose that meat to air, and you'll watch it transform to bright cherry-red oxymyoglobin as oxygen bonds to the protein's iron component.

If you're seeing brown or tan colors, that's metmyoglobin forming in low-oxygen conditions, where the iron has oxidized. This isn't just about oxygen, though – myoglobin's also ready to bond with other molecules. When carbon monoxide or nitric oxide enters the picture, they'll create stable color compounds that resist change, which is why cured meats maintain their color so well.

The stability of these color changes depends on several factors you'll need to take into account. The meat's pH, storage temperature, and the age of the animal all play significant roles.

Even after slaughter, ongoing enzymatic activity and competition for oxygen from muscle cell mitochondria continue to influence these color transformations.

Moisture Impact on Smoke Penetration

Maintaining proper moisture levels plays an essential role in how smoke molecules penetrate meat during smoking. When your meat's surface is moist, it becomes more receptive to smoke particles, as water molecules help grab and hold onto passing smoke chemicals. This process creates a "sticky" surface that enhances smoke absorption while preventing the premature formation of a dense bark that could block smoke penetration.

You'll get better smoke penetration by keeping the surface wet through methods like spritzing or mopping with water-based solutions once per hour. These techniques can extend your cooking time by 10-20%, particularly in low-and-slow cooking below 250°F. Using a water pan in your smoker helps maintain consistent humidity levels and promotes smoke ring formation.

The science behind this interaction is straightforward: moist smoke particles and combustion gases condense and dissolve more effectively on wet surfaces, allowing deeper penetration through diffusion. This process continues until the meat reaches about 170°F internally, after which myoglobin loses its ability to retain oxygen.

For ideal results, you'll want to maintain moisture throughout the smoking process, whether through natural humidity or controlled methods.

Chemical Bonding During Smoking

Beyond surface moisture, the molecular magic of smoking happens through precise chemical interactions between smoke compounds and meat proteins. When smoke contacts your meat, phenols and other smoke components begin modifying the protein structures on the surface. These interactions primarily affect the outer layers, where smoke molecules can penetrate and bond with protein surfaces.

You'll find that the smoking process creates a unique reducing environment that influences disulfide bonds, which are essential connections between protein molecules. While smoke's reducing agents won't break existing disulfide bonds, they can prevent new ones from forming, contributing to meat tenderness.

The process gets even more interesting when phenols like guaiacol start coagulating proteins and fixing aromatic compounds to the meat's surface.

The Maillard reaction plays an important role too, as smoke enhances the chemical reactions between your meat's amino acids and reducing sugars. This creates new flavor compounds and that characteristic brown surface.

During the slow cooking process, collagen breaks down into gelatin, while smoke molecules continue bonding with proteins, ultimately developing that distinctive smoky flavor and tender texture you're looking for.

Preservation Through Molecular Transformation

The molecular transformation of meat during smoking creates multiple preservation barriers against spoilage. You'll find that smoke compounds bond with the meat's surface proteins, forming a protective layer that prevents microbial growth. The phenols in smoke act as antioxidants, while formaldehyde and acetic acid lower the surface pH, creating an inhospitable environment for bacteria.

| Smoke Component | Preservation Effect |

|---|---|

| Phenols | Prevents fat oxidation, blocks bacterial growth |

| Formaldehyde | Lowers surface pH, creates antimicrobial barrier |

| Acetic Acid | Reduces pH, inhibits microorganism growth |

| Heat | Kills surface bacteria, accelerates drying |

| Volatile Compounds | Forms protective surface layer |

When you combine smoking with salt-curing, you'll achieve even better preservation through osmosis. The salt draws out moisture, while smoke compounds create chemical bonds with meat proteins. This dual action means your properly smoked and cured meat can last for weeks in the refrigerator. Without proper curing, though, you'll find the preservation effects are limited to just a few days. The key to successful preservation lies in the complete molecular transformation through both smoke penetration and proper salt integration.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can Different Types of Wood Affect the Strength of Smoke-Protein Bonds?

Yes, different woods affect bond strength. You'll find hardwoods like oak and hickory create stronger smoke-protein bonds due to their higher phenolic compound content, while softwoods form weaker bonds and produce undesirable flavors.

Does Freezing Meat Before Smoking Impact Its Ability to Bond With Smoke?

While freezing won't greatly impact your meat's ability to bond with smoke molecules, you'll need to properly thaw it first. The chemical reactions between smoke and proteins remain effective, though texture may be slightly affected.

How Do Marinades Influence the Molecular Bonding Between Smoke and Proteins?

You'll get better smoke-protein bonding when marinades break down surface proteins. Acidic and enzymatic marinades create more binding sites by increasing porosity and exposing protein structures for smoke molecules to attach.

Can Artificial Smoke Create the Same Protein Bonds as Natural Wood Smoke?

No, you won't get identical protein bonds with artificial smoke. While liquid smoke adds flavor, it can't replicate the complex Maillard reactions and myoglobin binding that occur during natural wood smoking processes.

Does Aging Meat Affect Its Capacity to Form Bonds With Smoke Molecules?

Yes, when you age meat, it'll affect smoke molecule bonding. The breakdown of proteins and increased porosity can enhance smoke penetration and flavor integration, though you'll still get effective bonds with properly aged meat.

In Summary

You've learned how smoke molecules chemically bond with meat proteins through complex interactions. These reactions transform your food at the molecular level, creating that distinctive smoky flavor and color you love. When you understand the role of temperature, moisture, and time in forming these bonds, you'll master the science of smoking meat and achieve better results in your cooking.

Leave a Reply