Your sourdough gets its distinctive tang from lactic acid fermentation, where beneficial bacteria and wild yeasts work together to transform flour and water. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) outnumber yeasts 100 to 1 in mature starters, breaking down sugars into acids that create that signature sour flavor. You'll find two types of LAB at work: homofermentative bacteria producing pure lactic acid for a mild tang, and heterofermentative bacteria creating both lactic and acetic acids for sharper notes. Temperature and hydration levels play vital roles – warmer, wetter conditions favor lactic acid, while cooler, drier environments boost acetic acid. Understanding these fundamentals opens up a world of flavor possibilities in your sourdough journey.

The Microbial Community

The microbe universe within sourdough starters thrives with two main players: lactic acid bacteria and wild yeasts. You'll find over 50 species of lactic acid bacteria, primarily from the Lactobacillus genus, working alongside more than 20 species of yeast, including Saccharomyces and Candida. In a mature starter, lactic acid bacteria outnumber yeasts by about 100 to 1.

These microbes don't just appear from nowhere – they're primarily hitchhiking on your flour. While some microorganisms come from the air, your hands, or your kitchen environment, the flour you use contributes the majority of the microbial community. That's why different flours can lead to distinctly different starter characteristics. These microbial communities have been essential in bread making for millennia, helping preserve food through fermentation.

You'll notice that even starters from the same neighborhood can develop unique microbial profiles. The community in your starter isn't static; it evolves over time through microbial succession and adapts to environmental conditions.

However, when you maintain consistent feeding schedules, temperature, and hydration levels, you'll develop a stable culture dominated by heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria like L. fermentum and L. plantarum.

Understanding Lactic Acid Production

Every aspect of lactic acid production in sourdough starts with the metabolic activity of lactic acid bacteria (LAB).

You'll find two types of LAB at work in your starter: homofermentative bacteria, which produce only lactic acid from 6-carbon sugars, and heterofermentative bacteria, which create a mix of lactic acid, carbon dioxide, and either ethanol or acetic acid from both 5- and 6-carbon sugars.

When you're maintaining your starter, you're actually managing these bacterial processes. Higher hydration levels and temperatures around 90°F (32°C) will boost LAB activity, leading to more lactic acid production. Daily feeding schedules help maintain consistent fermentation patterns and predictable acid production.

You'll notice this as a milder, yogurt-like tang in your bread. If you're looking for a sharper flavor, you can reduce hydration or lower the temperature, which will encourage more acetic acid production.

The mineral content in your flour matters too, especially if you're using whole grain varieties.

These minerals act as natural buffers, allowing bacteria to produce more acid without killing themselves off. As LAB outnumber yeasts 100 to 1 in mature starters, they're the primary drivers of both your bread's flavor and its natural preservation system.

Starting Your Wild Culture

You'll begin your wild sourdough culture by combining equal parts whole wheat flour and room-temperature water in a clean jar, mixing until smooth.

Using organic unbleached bread and whole wheat flour is essential for optimal fermentation.

After the initial 24-hour rest period, you must maintain a consistent feeding schedule, discarding half the mixture and adding fresh flour and water in your chosen ratio (1:2:2 or 1:4:4) daily.

Your culture will show signs it's ready for baking when it reliably doubles in size within 4-8 hours of feeding and displays a bubbly surface with a pleasant, tangy aroma.

Flour and Water Basics

Starting a wild sourdough culture begins with two simple ingredients: flour and water mixed at a 1:1 ratio by weight. This 100% hydration creates the perfect environment for beneficial microorganisms to thrive.

You'll need a digital scale for accurate measurements and a glass jar with loose covering to allow airflow while protecting against contaminants.

Your water choice matters greatly. If you're using tap water, let it sit uncovered for 24 hours to remove chlorine, which can inhibit microbial growth. Alternatively, you can use filtered or bottled water. Warm water around 85°F helps kickstart fermentation and maintains consistency in your starter's development.

For the best results in creating your starter, follow these key steps:

- Choose your flour carefully – whole wheat flour or a combination with all-purpose flour enhances fermentation.

- Maintain a consistent warm temperature between 70-75°F.

- Mix thoroughly until no dry clumps remain.

- Use an offset spatula to scrape down jar sides for complete incorporation.

This careful attention to ingredients and process creates an ideal environment where wild yeasts and bacteria can establish themselves, leading to a stable, active culture that'll produce that characteristic sourdough tang.

Daily Feeding Schedule

Once you've established your initial flour and water mixture, maintaining a consistent feeding schedule becomes the next vital focus.

You'll need to feed your starter every 12-24 hours when keeping it at room temperature, with warmer environments requiring more frequent feedings. If you're baking regularly, stick to a twice-daily schedule to maintain peak activity.

Your feeding routine should follow a precise ratio of equal parts flour and water for 100% hydration.

You'll want to combine 70g white flour, 30g rye flour, and 100g room temperature water, ensuring you mix thoroughly to eliminate any dry clumps. If your starter seems sluggish, try reducing the hydration to 85-90% temporarily.

For less frequent baking, you can store your starter in the refrigerator, reducing feedings to once a week.

When you're ready to use it again, you'll need to revive it with 2-3 feedings at 12-hour intervals. Remember to let refrigerated starters warm to room temperature before feeding.

Keep your container loosely covered to maintain proper airflow during the fermentation process, which is essential for healthy bacterial activity.

Signs of Active Growth

Several key indicators reveal when your sourdough starter has developed healthy microbial activity.

You'll notice significant volume changes, with your starter doubling or even tripling in size within 4-6 hours after feeding. In warmer conditions, this growth can occur in as little as 2 hours. The starter will develop a dome-like shape at its peak and feel especially light due to trapped carbon dioxide.

When examining texture and consistency, look for these reliable signs:

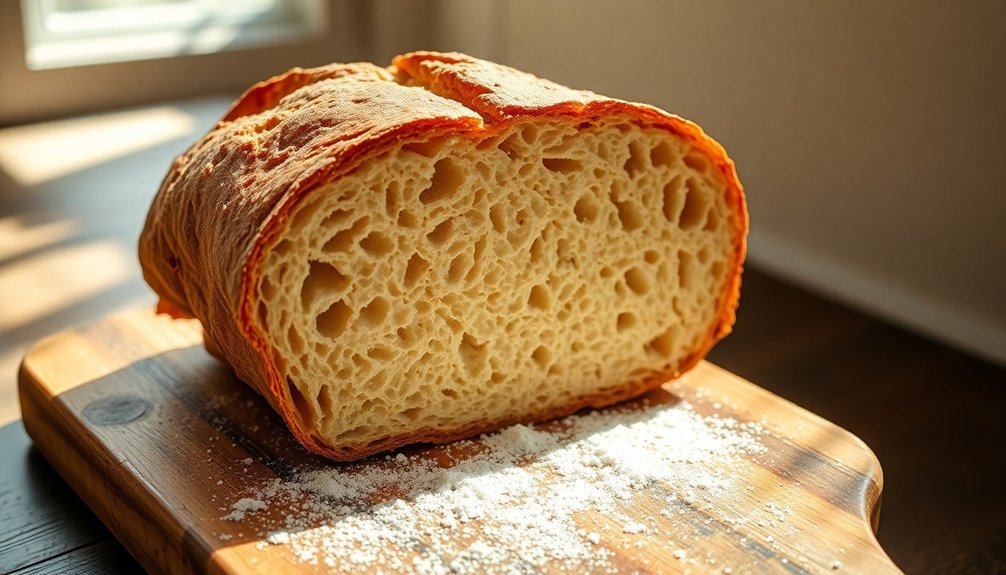

- A spongy, honeycomb network of bubbles visible through the jar's sides

- Large bubbles that break on the surface when the starter reaches its peak

- A mousse-like, aerated texture throughout

- A thickness similar to warm peanut butter

Your nose is another valuable tool in evaluating starter health. A properly active starter will emit a pleasant, yeasty aroma.

Avoid using starters that smell like acetone, parmesan cheese, or stinky socks, as these indicate unhealthy fermentation. You can confirm your starter's readiness with the float test – a spoonful should float when dropped in water.

Remember that environmental factors like temperature and flour type will influence your starter's behavior.

Managing Acidity Levels

Managing the acidity levels in sourdough requires balancing four key factors: flour composition, starter maintenance, hydration, and microbial activity. You'll find that each element plays an essential role in determining how sour your bread becomes.

| Factor | For More Sour | For Less Sour |

|---|---|---|

| Flour Type | Use whole wheat/grain | Use refined flour |

| Starter Usage | Less starter, longer ferment | More starter, shorter ferment |

| Hydration | Lower hydration (stiffer) | Higher hydration (wetter) |

| Timing | Let starter go past peak | Use at peak activity |

Your flour choice greatly impacts acidity – whole grains contain more minerals and pentosans, which buffer acid production and provide additional food for bacteria. If you're aiming for tangier bread, you'll want to reduce your starter amount and extend fermentation time. The hydration level you choose affects bacterial activity – lower hydration promotes more acetic acid production, while higher hydration favors milder lactic acid. You can also control sourness through your starter's maintenance schedule – using it at peak produces milder flavors, while letting it ferment longer develops stronger acidity. The key is understanding how these factors interact with your starter's microbial community.

Fermentation Time and Temperature

You'll find that managing fermentation time and temperature is essential for achieving the right balance of flavors in your sourdough, with ideal fermentation occurring between 76-80°F.

When you're working with warmer temperatures (74-78°F), you can expect faster fermentation times of 2-5 hours, while colder temperatures will greatly slow down the microbial activity and extend your fermentation period.

Your control over these variables directly affects the growth rate of beneficial bacteria and wild yeasts, ultimately determining the quality and character of your final loaf.

Time-Temperature Balance Essential

Sourdough's success hinges on the delicate balance between fermentation time and temperature. You'll achieve excellent results by maintaining temperatures between 75-78°F (24-26°C), where both yeast and bacteria thrive. At this range, you're creating ideal conditions for flavor development and proper fermentation rates.

You can control your fermentation process by adjusting four key variables:

- Water temperature – Use the formula: (Target Dough Temperature x 3) – (Room Temperature + Flour Temperature)

- Ambient temperature – Find a consistent spot in your kitchen or use a proofing box

- Hydration levels – Increase in warm conditions, decrease in cool conditions

- Mixing friction – Account for heat generated during mechanical mixing

If you're working in warmer conditions above 78°F (26°C), you'll notice faster fermentation and may need to reduce your timing. Conversely, temperatures below 70°F (21°C) will slow down the process, requiring longer fermentation periods.

Don't let your dough exceed 90°F (32°C), as this can kill the yeast. For enhanced flavor development, consider cold fermentation, which offers better control and can fit more easily into your schedule.

Cold Vs Warm Fermentation

Understanding the differences between cold and warm fermentation opens up new possibilities for controlling your sourdough's flavor and texture. When you ferment at warm temperatures (74-78°F), you'll activate vigorous yeast growth, resulting in faster fermentation and pronounced bread rise within 2-5 hours. In contrast, cold fermentation (below 39°F) slows down yeast activity while bacteria continue producing acetic acid, creating tangier flavors over 24+ hours.

| Factor | Warm Fermentation (74-78°F) | Cold Fermentation (Below 39°F) |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | 2-5 hours | 24+ hours |

| Rise | Significant | Minimal |

| Flavor | Balanced | More sour, complex |

| Crumb | Open structure | Denser texture |

| Acid Production | Moderate | High acetic acid |

You'll need to monitor dough temperature carefully for consistent results. Using a thermometer helps you maintain the ideal temperature range for your desired outcome. While bulk fermentation works best at room temperature, you can leverage cold fermentation in your refrigerator to develop deeper flavors. By adjusting water temperature and controlling fermentation conditions, you'll achieve predictable results and customize your bread's characteristics.

Controlling Microbial Growth Rate

Mastering microbial growth in sourdough requires careful attention to both time and temperature variables.

You'll find that different bacteria thrive at specific temperature ranges, with most lactic acid bacteria preferring 18-22°C. When you ferment at warmer temperatures above 22°C, you'll encourage Lactobacillus species to dominate, while cooler temperatures favor yeast growth and acetic acid production.

Time plays a significant role in determining which bacteria will dominate your culture. Early fermentation stages favor homofermentative bacteria like Pediococcus, while longer fermentation allows heterofermentative species to take over.

You'll need to manage these factors carefully to achieve your desired flavor profile.

To optimize your fermentation process, consider these key control points:

- Keep temperatures between 18-22°C for balanced bacterial growth

- Extend fermentation time to increase sourness and complexity

- Monitor acid levels, as they'll naturally slow bacterial activity

- Adjust temperature based on whether you want more lactic acid (warmer) or acetic acid (cooler)

Remember that higher temperatures accelerate acid production, while cooler temperatures slow down the process but can lead to more complex flavors.

Gluten Development During Fermentation

Three key processes work together during sourdough fermentation to develop gluten: enzymatic activity, bacterial fermentation, and physical manipulation.

During fermentation, your starter's lactic acid bacteria and wild yeasts interact with flour proteins to form strong gluten networks through hydrogen bonds and disulfide cross-links.

You'll want to maintain a delicate balance, as over-fermentation can trigger enzyme activity that breaks down these gluten structures, while under-fermentation won't allow enough development.

You can enhance gluten development through various techniques. The stretch and fold method, performed every 15-30 minutes for 4-6 sets, helps strengthen the dough structure.

For high-hydration doughs, you'll find the coil fold particularly effective, as it's gentler and preserves the bubbles formed during fermentation.

Your choice of ingredients greatly impacts gluten formation. Strong bread flours create robust networks that can withstand longer fermentation times.

You can boost gluten content by adding essential wheat gluten, especially when working with whole grains.

Remember that proper hydration levels and salt addition are critical for ideal gluten development, while cold fermentation allows for extended processing without risking gluten breakdown.

Harnessing Natural Preservation Benefits

Every sourdough baker benefits from lactic fermentation's natural preservative properties. When you're making sourdough, lactic acid bacteria create an acidic environment that keeps your bread naturally protected from harmful microorganisms. The resulting low pH, typically between 3.5 and 5, makes it impossible for dangerous bacteria like Staphylococcus to survive and thrive in your loaf.

You'll find that this natural preservation process offers multiple advantages for your sourdough:

- Your bread stays fresh longer without artificial preservatives

- The acidic environment prevents the growth of harmful pathogens

- You can easily detect any failed fermentation through distinct off-putting odors

- The preservation method maintains the bread's nutritional integrity

The preservation benefits don't stop at safety alone. You're also getting enhanced nutritional value as the fermentation process breaks down anti-nutrients like phytates, making minerals more bioavailable.

The lactic acid bacteria produce additional vitamins and beneficial compounds that support your digestive health.

What's more, you'll notice that properly fermented sourdough develops complex flavors while maintaining its keeping qualities, thanks to the natural antimicrobial properties of lactic acid.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I Revive a Neglected Sourdough Starter That Hasn't Been Fed?

Yes, you can revive your neglected starter. Remove most of it, keep about 1/2 cup, and start feeding it twice daily with equal parts flour and water until it's bubbly and doubles in size.

Why Does My Sourdough Smell Like Alcohol or Acetone Sometimes?

Your sourdough will smell like alcohol during normal fermentation as yeast converts sugars. If you're getting acetone smells, it's likely starving – feed it more frequently to maintain a healthy bacterial balance.

How Do Different Flour Types Affect the Sourness of Bread?

You'll get more sour bread using rye and whole wheat flours due to their higher ash content and complex nutrients. They boost bacterial activity and acid production, while white flour produces milder flavors.

Does Altitude Affect Sourdough Fermentation and Starter Maintenance?

Yes, altitude greatly affects your sourdough. You'll notice faster fermentation due to lower air pressure, and you'll need to adjust hydration levels, reduce starter amounts, and monitor proofing times more carefully at higher elevations.

Can I Use Commercial Yeast to Jumpstart My Sourdough Culture?

While you can add commercial yeast to jumpstart your sourdough culture, it'll disrupt the natural microbial balance and reduce the authentic sourdough flavor. You're better off developing a starter with wild yeasts naturally.

In Summary

You've learned how lactic fermentation creates the complex flavors in sourdough through the interaction of wild yeasts and bacteria. By managing time, temperature, and feeding schedules, you'll control acidity levels to achieve your desired tang. With practice, you'll understand how the microbial community in your starter develops gluten and naturally preserves your bread, making each loaf uniquely yours.

Leave a Reply